What Is the Best Way to Wash a House

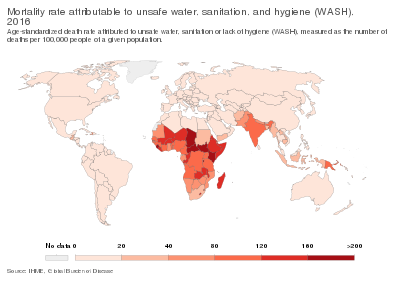

Mortality rate attributable to unsafe h2o, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).[1]

Wash (or Watsan, WaSH) is an acronym that stands for "water, sanitation and hygiene". Universal, affordable and sustainable access to WASH is a cardinal public wellness issue within international evolution and is the focus of the offset two targets of Sustainable Development Goal vi (SDG 6).[two] Targets vi.1 and 6.2 aim at equitable and accessible h2o and sanitation for all. "Admission to Launder" includes safe water, adequate sanitation and hygiene didactics. Improving access to WASH services tin improve health, life expectancy, student learning, gender equality, and other of import issues of international development.[three] This can reduce illness and death, and also affect poverty reduction and socio-economic development.[4] Challenges include providing services to urban slums, improper direction of water distribution systems, failures of Launder systems over time, providing equitable admission to drinking water supply and gender issues. Launder services accept to be provided to household locations only also to schools, healthcare facilities, work places, markets, prisons, train stations, public locations etc.

In 2022 the Globe Health System (WHO) estimated that "i in 3 people, or 2.4 billion, are nevertheless without sanitation facilities" while 663 million people all the same lack access to safe and clean drinking h2o.[5] [6] In 2017, this gauge changed to 2.3 billion people without sanitation facilities and 844 million people without admission to safe and clean drinking water.[7]

Lack of sanitation contributes to about 700,000 child deaths every twelvemonth due to diarrhea, mainly in developing countries. Chronic diarrhea can have long-term negative effects on children, in terms of both physical and cognitive development.[4] In addition, lack of Launder facilities at schools can prevent students (especially girls) from attending school, and reduce their educational achievements and later work productivity.[viii]

Definition and purpose [edit]

Women at a Village Pond in Matlab, Bangladesh: The woman on the right is putting a sari filter onto a water-collecting pot (or kalash) to filter h2o for drinking.

The concept of Launder groups together water supply, sanitation, and hygiene because the touch of deficiencies in each area overlap strongly (Launder is an acronym that uses the first letters of "h2o, sanitation and hygiene"). Addressing these deficiencies together tin achieve a strong positive impact on public health.

Wellness aspects [edit]

Overview [edit]

Effective sanitation separates human excreta from contact with people, and this can preclude many diseases such as (simply not only) waterborne diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) collated information on sanitation and health in their "Guidelines on Sanitation and Health".[9] Health impacts of the lack of safe sanitation systems can exist grouped into iii categories: Directly affect (infections), sequelae (conditions caused by preceding infection) and broader well-being.[ix] : 2 These categories include the following:[9] : 2

- Direct impact: Fecal-oral infections, helminth infections and insect vector diseases (meet also waterborne diseases, which tin contaminate drinking water)

- Conditions acquired by preceding infection: Stunting/ growth faltering, consequences of stunting (obstructed labour, low birthweight), impaired cognitive part, pneumonia (related to repeated diarrhea in undernourished children), anaemia (related to hookworm infections)

- Broader well-beingness: Immediate: Anxiety, sexual assail (and related consequences), agin nascency outcomes; Long-term (school absence, poverty, decreased economic productivity, antimicrobial resistance)

Acceptable sanitation in conjunction with good hygiene and safe water are essential to good health. Lack of proper sanitation causes diseases. Most of the diseases resulting from sanitation have a direct relation to poverty. The lack of clean h2o and poor sanitation causes many diseases and the spread of diseases. It was estimated in 2002 that inadequate sanitation was responsible for 4.0 pct of deaths and 5.7 percent of disease burden worldwide.[10]

Open defecation – or lack of sanitation – is a major cistron in causing various diseases, most notably diarrhea and intestinal worm infections.[eleven] [12]

Wash-attributable brunt of diseases and injuries [edit]

A study by World Health Organization in 2022 found that "Worldwide, one.nine million deaths and 123 meg DALYs could take been prevented in 2022 with adequate Launder. The Wash-attributable affliction brunt amounts to three.3% of global deaths and iv.half dozen% of global DALYs. Amidst children nether v years, WASH-attributable deaths represent 13% of deaths and 12% of DALYs."[13]

An earlier study from 2002 had estimated that up to 5 million people dice each twelvemonth from preventable waterborne diseases.[14]

Twelve diseases associated with inadequate Wash where "population attributable fractions" tin be quantified:[13]

- Diarrheal diseases

- Respiratory infections

- Soil-transmitted helminth infections - Approximately 2 billion people are infected with soil-transmitted helminths worldwide; they are transmitted past eggs nowadays in human feces which in turn contaminate soil in areas where sanitation is poor.[15]

- Malaria

- Trachoma

- Schistosomiasis

- Lymphatic filariasis

- Onchocerciasis

- Dengue

- Japanese encephalitis

- Protein–free energy malnutrition

- Drowning

Diseases where adverse health outcomes or injuries linked to inadequate Launder are described just not yet quantified:[13]

- Arsenicosis

- Fluorosis

- Legionellosis

- Leptospirosis

- Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E

- Cyanobacterial toxins

- Lead poisoning

- Scabies

- Spinal injury

- Poliomyelitis

- Neonatal conditions (see also babe mortality) and maternal outcomes (such as maternal deaths)

- Other diseases (appropriate Launder is important for the command and intendance of nearly neglected tropical diseases)

Diarrhea, malnutrition and stunting [edit]

A kid receiving malnutrition treatment in Northern Kenya

Diarrhea, besides spelled diarrhoea, is the status of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day.[16] It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss.[16] Signs of dehydration oft begin with loss of the normal stretchiness of the skin and irritable behaviour.[16] This tin can progress to decreased urination, loss of skin color, a fast middle rate, and a subtract in responsiveness as it becomes more than severe.[16] Loose simply non-watery stools in babies who are exclusively breastfed, all the same, are normal.[sixteen]

Most 1.seven to 5 billion cases of diarrhea occur per yr.[sixteen] [17] [18] It is nigh common in developing countries, where immature children go diarrhea on average three times a year.[16] Total deaths from diarrhea are estimated at 1.26 million in 2013—downward from 2.58 1000000 in 1990.[19] In 2012, it was the second almost common cause of deaths in children younger than five (0.76 million or 11%).[16] [20] Frequent episodes of diarrhea are too a mutual cause of malnutrition and the most common crusade in those younger than five years of age.[16] Other long term problems that can result include stunted growth and poor intellectual evolution.[20]

What is diarrhea, how is it caused, treated and prevented (come across also script).

Diarrhea is primarily transmitted through fecal-oral routes. In 2011, infectious diarrhea resulted in almost 0.seven million deaths in children under v years former and 250 1000000 lost school days.[11] [21] This equates to about 2000 kid deaths per mean solar day.[22] Children suffering from diarrhea are more vulnerable to become underweight (due to stunted growth).[23] [24] This makes them more vulnerable to other diseases such equally acute respiratory infections and malaria. Chronic diarrhea tin take a negative effect on child development (both physical and cerebral).[4]

Numerous studies have shown that improvements in drinking h2o and sanitation Wash lead to decreased risks of diarrhea.[25] Such improvements might include for instance use of water filters, provision of loftier-quality piped water and sewer connections.[25] Diarrhea can be prevented - and the lives of 525,000 children annually be saved (estimate for 2017) - by improved sanitation, clean drinking water, and manus washing with soap.[26] In 2008 the same figure was estimated as i.5 one thousand thousand children.[27]

The combination of direct and indirect deaths from malnutrition acquired by unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene (Wash) practices was estimated by the Globe Wellness Organization in 2008 to atomic number 82 to 860,000 deaths per year in children nether v years of age.[28] The multiple interdependencies between malnutrition and infectious diseases make information technology very difficult to quantify the portion of malnutrition that is caused by infectious diseases which are in plough caused past unsafe WASH practices. Based on expert opinions and a literature survey, researchers at WHO arrived at the conclusion that approximately half of all cases of malnutrition (which often leads to stunting) in children under five is associated with repeated diarrhea or abdominal worm infections equally a result of unsafe h2o, inadequate sanitation or insufficient hygiene.[28]

Neglected tropical diseases [edit]

Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions help to prevent many neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), for example soil-transmitted helminthiasis.[29] An integrated arroyo to NTDs and WASH benefits both sectors and the communities they are aiming to serve.[30] This is specially true in areas that are endemic with more than one NTD.[29]

In August 2015, the Globe Health Organization (WHO) unveiled a global strategy and activeness programme to integrate WASH with other public health interventions in society to advance emptying of NTDs.[31] The plan aims to intensify control or eliminate certain NTDs in specific regions by 2020.[32] It refers to the NTD roadmap milestones that included for example eradication of dracunculiasis by 2022 and of yaws by 2020, elimination of trachoma and lymphatic filariasis as public health bug by 2020, intensified control of dengue, schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases.[33] The plan consists of four strategic objectives: improving awareness of benefits of articulation WASH and NTD deportment; monitoring Launder and NTD deportment to track progress; strengthening evidence of how to evangelize effective WASH interventions; and planning, delivering and evaluating WASH and NTD programmes with involvement of all stakeholders.[34] The aim is to use synergies between WASH and NTD programmes.

Prove regarding wellness outcomes [edit]

There is debate in the academic literature about the effectiveness on wellness outcomes when implementing Launder programs in depression- and middle-income countries. Many studies provide poor quality evidence on the causal impact of WASH programs on wellness outcomes of interest. The nature of WASH interventions is such that loftier quality trials, such every bit randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are expensive, difficult and in many cases non ethical. Causal impact from such studies are thus prone to being biased due to residuum misreckoning.[ citation needed ] Blind studies of WASH interventions too pose ethical challenges and difficulties associated with implementing new technologies or behavioral changes without participant's knowledge.[35] Moreover, scholars propose a need for longer-term studies of engineering science efficacy, greater analysis of sanitation interventions, and studies of combined furnishings from multiple interventions in order to more sufficiently gauge Wash health outcomes.[36]

Many scholars have attempted to summarize the evidence of Wash interventions from the limited number of loftier quality studies. Hygiene interventions, in particular those focusing on the promotion of handwashing, appear to be especially effective in reducing morbidity. A meta-assay of the literature found that handwashing interventions reduced the relative take chances of diarrhea by approximately forty%.[37] [35] Similarly, handwashing promotion has been found to be associated with a 47% decrease in morbidity. Still, a challenge with Wash behavioral intervention studies is an disability to ensure compliance with such interventions, peculiarly when studies rely on self-reporting of illness rates. This prevents researchers from concluding a causal relationship between decreased morbidity and the intervention. For example, researchers may conclude that educating communities almost handwashing is effective at reducing disease, just cannot conclude that handwashing reduces disease.[35] Bespeak-of-employ water supply and point-of-use water quality interventions also evidence similar effectiveness to handwashing, with those that include provision of prophylactic storage containers demonstrating increased illness reduction in infants.[36]

Specific types of water quality improvement projects can have a protective upshot on morbidity and mortality. A randomized control trial in India concluded that the provision of chlorine tablets for improving water quality led to a 75% decrease in incidences of cholera among the study population.[38] A quasi-randomized report on historical data from the United States also constitute that the introduction of clean water technologies in major cities was responsible for shut to one-half the reduction in total bloodshed and over three-quarters of the reduction in infant mortality.[39] Distributing chlorine products, or other water disinfectants, for use in the home may reduce instances of diarrhea.[40] However, most studies on water quality improvement interventions suffer from residual confounding or poor adherence to the machinery being studied. For instance, a study conducted in Nepal found that adherence to the use of chlorine tablets or chlorine solution to purify water was equally depression as 18.v% amongst program households.[38] A written report on a h2o well chlorination program in Guinea-Bissau in 2008 reported that families stopped treating water within their households because of the program which consequently increased their run a risk of cholera. It was concluded that well chlorination without proper promotion and education led to a imitation sense of security.[38]

Studies on the event of sanitation interventions lonely on health are rare.[37] When studies practice evaluate sanitation measures, they are mostly included equally part of a package of different interventions.[35] A pooled assay of the express number of studies on sanitation interventions suggest that improving sanitation has a protective effect on health.[41] [37] A UNICEF funded sanitation intervention (packaged into a broader WASH intervention) was too found to have a protective result on nether-v diarrhea incidence but not on household diarrhea incidence.[42]

Not-household locations [edit]

Schools [edit]

School toilets at Shaheed Monumia authorities secondary school, Tejgaon, Dhaka, People's republic of bangladesh)

School toilet at IPH schoolhouse and college, Mohakhali, Dhaka, People's republic of bangladesh)

Pupils in Medan, Indonesia, practice handwashing in class

WASH in schools, sometimes called SWASH or WinS, significantly reduces hygiene-related illness, increases student omnipresence and contributes to dignity and gender equality.[43] Launder in schools contributes to healthy, safety and secure school environments that can protect children from health hazards, corruption and exclusion. It also enables children to become agents of change for improving h2o, sanitation and hygiene practices in their families and communities.

Lack of WASH facilities can prevent students from attending schoolhouse, impose a burden on women, and diminish productivity.[8]

Data from over 10,000 schools in Zambia was analysed in 2022 and confirmed that improved sanitation provision in schools was correlated with high female-to-male person enrolment ratios, and reduced repetition and drop-out ratios, especially for girls.[44] The study thus confirmed the linkages between adequate toilets in schools and educational progression of girls.[44]

More than than one-half of all primary schools in the developing countries with available data do non accept adequate water facilities and virtually ii thirds lack adequate sanitation.[43] Fifty-fifty where facilities exist, they are frequently in poor status. Boys and girls are able to more fully participate in school when at that place is improved access to h2o.[45] : 24

Reasons for missing or poorly maintained h2o and sanitation facilities at schools in developing countries include lacking inter-sectoral collaboration; lacking cooperation between schools, communities and dissimilar levels of government; likewise every bit a lack in leadership and accountability.[46]

Strong cultural taboos around menstruation, which are nowadays in many societies, coupled with a lack of Menstrual Hygiene Direction services in schools, results in girls staying away from school during catamenia.[47]

Approaches [edit]

Methods to amend the state of affairs of Launder infrastructure at schools include on a policy level: broadening the focus of the education sector, establishing a systematic quality assurance arrangement, distributing and using funds wisely.[46] Other practical recommendations include: have a clear and systematic mobilization strategy, support the education sector to strengthen intersectoral partnerships, found a constant monitoring organisation which is located within the education sector, brainwash the educators and partner with the schoolhouse management.[46]

The support provided by development agencies to the government at national, state and district levels is helpful to gradually create what is commonly referred to every bit an enabling environment for Wash in schools. This includes audio policies, an advisable and well-resourced strategy, and effective planning. Such efforts need to be sustained over longer fourth dimension periods as ministries and departments of education are very large organizations, which generally show much inertia and are tedious to reform.[48] [49]

Success also hinges on local-level leadership and a genuine collective commitment of school stakeholders towards school development. Developing human and social capital amongst core school stakeholders is of import. This applies to students and their representative clubs, headmaster and teachers, parents and SMC members. Furthermore, other stakeholders have to be engaged in their straight sphere of influence, such equally: community members, customs-based organizations, educations official, local authorities.[50] [51]

Group handwashing [edit]

Supervised daily group handwashing in schools can be an effective strategy for edifice practiced hygiene habits, with the potential to lead to positive health and education outcomes for children.[52] This has for example been implemented in the "Essential Health Care Program" past the Department of Instruction in the Philippines.[53] Deworming twice a year, supplemented by washing hands daily with lather and brushing teeth daily with fluoride, is at the core of this national program. It has also been successfully implemented in Indonesia.[54] [55]

Approximately xl% of the world's population live without basic mitt washing facilities with soap and water at home.[56] Co-ordinate to the Globe Wellness Organization, over half of the people who live in rural areas in less developed parts of the world do not exercise hand washing methods due to a astringent lack of water and soap. Improving access to mitt washing and sanitation facilities in healthcare settings will significantly reduce infection and bloodshed rates, particularly in maternal and child health.[57]

Health facilities [edit]

The provision of adequate water, sanitation and hygiene is an essential part of providing basic health services in healthcare facilities. WASH in Health facilities aids in preventing the spread of infectious diseases as well equally protects staff and patients. Urgent activeness is needed to better Launder services in health facilities in developing countries.[58]

Co-ordinate to the World Health Organization, data from 54 countries in low and centre income settings representing 66,101 health facilities testify that 38% of wellness care facilities lack improved water sources, 19% lack improved sanitation while 35% lack access to water and soap for handwashing. The absenteeism of bones Launder civilities compromises the ability to provide routine services and hinders the ability to prevent and control infections. The provision of water in health facilities was the everyman in Africa, where 42% of healthcare facilities lack an improved source of water on-site or nearby. The provision of sanitation is lowest in the Americas with 43% of health care facilities lacking adequate services.[58]

In 2019, WHO estimated that: "I in four wellness care facilities lack bones water services, and one in 5 take no sanitation service – impacting 2.0 and 1.5 billion people, respectively." Furthermore, it is estimated that "health intendance facilities in depression-income countries are at least 3 times every bit probable to have no water service as facilities in higher resource settings". This is idea to contribute to the fact that maternal sepsis is twice as great in developing countries every bit information technology is in high income countries.[59] : vii

Barriers to providing Wash in wellness care facilities include: Incomplete standards, inadequate monitoring, disease-specific budgeting, disempowered workforce, poor Launder infrastructure.[59] : 14

The comeback of Wash standards inside health facilities needs to exist guided by national policies and standards as well as an allocated budget to better and maintain services.[58] A number of solutions exist that tin can considerably amend the health and safety of both patients and service providers at health facilities.

- Availability of safe water: In that location is a demand for improved h2o pump systems within health facilities. Provision of safe water is necessary for drinking but also for use in surgery and deliveries, food preparation, bathing and showering.[60]

- Improved handwashing practices among healthcare staff must exist implemented through proper orientation and training. Functional mitt washing stations at strategic points of care inside the health facilities must exist provided. In low resource settings, a sink or basin with water and soap or paw sanitizer need to be bachelor at points of care and toilets.[sixty]

- Waste material organisation management: Proper health care waste direction and the safe disposal of excreta and waste h2o is crucial to preventing the spread of disease.[61] Waste matter should exist safely separated within large bins in the consultation expanse and sharp objects and infectious wastes disposed of properly and safely.[60]

- Hygiene promotion: Articulate and practical communication with patients and visitors, including staff, about hygiene promotion within the bounds should be implemented.[61]

- Accessibility to toilets: Accessible and clean toilets, separated by gender, in sufficient numbers for staff, patients and visitors.[61] Improved sanitary facilities that are usable, separate for patients and staff, separate for women and allowing menstrual hygiene management, and coming together the needs of disabled people.[60]

Challenges [edit]

Urban slums [edit]

Waiting in line for 2 hours to collect water from a standpipe

Role of the reason for slow progress in sanitation may exist due to the "urbanization of poverty", as poverty is increasingly concentrated in urban areas.[62] Migration to urban areas, resulting in denser clusters of poverty, poses a challenge for sanitation infrastructures that were not originally designed to serve and so many households, if they existed at all.

There are three main barriers to improvement of urban services in slum areas: Firstly, bereft supply, peculiarly of networked services. Secondly, there are usually demand constraints that limit people'due south admission to these services (for instance due to low willingness to pay). Thirdly, there are institutional constraints that prevent the poor from accessing adequate urban services.[63]

Water distribution systems [edit]

Improper management of water distribution systems in developing nations can exacerbate the spread of h2o-borne diseases. The Earth Health Arrangement estimates that 25%-45% of water in distribution lines is lost through leaks in developing countries. These leaks tin can allow for contaminated water and pathogens to enter the distribution pipes, peculiarly when ability outages result in a loss of pressure level in the water supply pipes. Cross-contagion of wastewater into beverage h2o lines has resulted in major disease outbreaks, such as a Typhoid fever outbreak in Dushanbe, Tajikistan in 1997.[64]

Failures of Wash systems [edit]

National authorities mapping and monitoring efforts, equally well as post-project monitoring by NGOs or researchers, accept identified the failure of water supply systems (including h2o points, wells and boreholes) and sanitation systems equally major challenges. Many water and sanitation systems are unsustainable, failing to provide extended health benefits to communities in the long-term. This has been attributed to financial costs, inadequate technical training for operations and maintenance, poor use of new facilities and taught behaviors, and a lack of community participation and ownership.[65]

Admission to WASH services likewise varies internally within nations depending on socio-economic status, political power, and level of urbanization. A 2004 estimate past UNICEF stated that urban households are 30% and 135% more than likely to accept access to improved water sources and sanitation respectively, as compared to rural areas. Moreover, the poorest populations cannot afford fees required for performance and maintenance of Launder infrastructure, preventing them from benefitting even when systems exercise exist.[64]

Equitable admission to drinking water supply [edit]

A global monitoring report past the Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation of WHO and UNICEF published in 2022 stated that 435 million people used unimproved sources for their drinking water, and 144 million still used surface water.[66] Reducing inequalities in basic water, sanitation and hygiene services is a longstanding WASH sector objectives.[66] : eleven Such inequalities are for example related to income level and gender. For example, in 24 countries where disaggregated data was available, bones h2o coverage amidst the richest wealth quintile was at to the lowest degree twice every bit loftier as coverage among the poorest quintile.[66]

The human rights to h2o and sanitation prohibit discrimination on the grounds of "race, color, sexual activity, linguistic communication, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, nativity, inability or other condition". These are all dimensions of inequality in Wash services.[66] : 13

Dealing with inequalities of water access falls under international human being rights law. In 2000, the Second World H2o Forum in The Hague concluded that women are the master users of domestic water, that women used water in their key food production roles, and that women and children were the most vulnerable to h2o-related disasters.[67] At the International Briefing on Water and the Environment, the Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Evolution included "Women Play a central part in the provision direction and safeguarding of h2o" as one of four principles.[68]

Water supply schemes in developing nations take shown higher success when planned and run with full participation of women in the affected communities. For example, a study including 88 communities in 14 countries showed that projects where men and women from intended user households were included in selection of site facilities, and where h2o projects were initiated past user households, rather than by external agencies or local leaders, achieved a concluding higher admission to services than those that did not.[69]

Gender [edit]

The lack of accessible, sufficient, clean and affordable water supply has adverse impacts specifically related to women in developing nations. Information technology is estimated that 263 one thousand thousand people worldwide spent over xxx minutes per circular trip to collect water from an improved source.[7] : 3 In sub-Saharan Africa, women and girls carry water containers for an boilerplate of three miles each twenty-four hours, spending 40 billion hours per year on water collection (walking to the water source, waiting in line, walking back).[seventy] : 14 The time to collect water can come up at the expense of instruction, income generating activities, cultural and political interest, and residuum and recreation.[71] : ii For example, in low-income areas of Nairobi, women carry 44 pound containers of water back to their homes, taking anywhere between an hour and several hours to expect and collect the h2o.[72] : 733

In many places of the world, getting and providing water is considered "women's work," and so gender and water admission are intricately linked.[73] : 256 H2o gathering and supply to family units remains primarily a woman's chore in less adult countries where water gathering is considered a chief chore.[73] : 256 This h2o work is also largely unpaid household work based on patriarchal gender norms and oftentimes related to domestic work, such as laundry, cooking and childcare.[45] : five Areas that rely on women to primarily collect h2o include countries in Africa, South Asia and in the Middle East.[45] : 4

Gender norms tin can negatively affect how men and women admission h2o through such beliefs expectations along gender lines—for instance, when water collection is a woman's chore, men who collect water may face up discrimination for performing perceived women's work.[74] For instance, women are likely to be deterred from inbound water utilities in developing countries because "social norms prescribe that information technology is an expanse of work that is not suitable for them or that they are incapable of performing well".[75] : 13 Withal, a written report by Globe Bank in 2022 has constitute that the proportion of female water professionals has grown in the by few years.[75] : x

In many societies, the task of cleaning toilets falls to women or children, which tin can increase their exposure to disease.[74] : 19

Woman collecting water in Kenya.

Gender-sensitive approaches to water and sanitation have proven to be cost effective.[76]

Many women's rights and water advocacy organizations accept identified water privatization as an area of business concern, sometimes alleging negative effects that specifically bear on women.[71]

The World Bank Gender and Evolution Grouping has addressed gender issue at an institutional level, citing successful "Gender-Mainstreaming" efforts in many of its H2o Supply and Sanitation projects. Already in 1996, Worldbank published a "Toolkit on Gender in H2o and Sanitation".[77]

The United nations Interagency Network on Women and Gender Equality (IANWGE) established the Gender and Water Task Forcefulness in 2003. The Chore Force became a Un-Water Job Strength and took responsibility for the gender component of International Water for Life Decade (2005-1015).[78] The Task Force's mandate ended in 2022 and the Job Forces later turned into Experts Groups (at that place is no Good Grouping on gender).

Country policy examples [edit]

A report in 2003 assessed the trends in gender mainstreaming at policy and institutional levels. Information technology also touched on the parallel trend towards Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM). The study concluded that:

"What is happening in South Africa is heady. [...] Now it is leading the field and pioneering its ain versions of the Environmental Reserve, and complimentary basic sanitation and water services for the very poor. Other countries (Zambia, People's republic of bangladesh, Uganda, ..) are demonstrating commitments to the gender and water link, but facing problems in carrying the principles through the institutional and legislative bondage."[79]

In Uganda, the National Water Policy has the total participation of women at all levels as one of its principles.[79]

Violence against women [edit]

Women and girls normally acquit the responsibility for collecting water, which is frequently very time-consuming and arduous, and can as well be unsafe for them.[80] Women and girls who collect water may also face concrete set on and sexual set on along the manner (violence confronting women).[81] This includes vulnerability to rape when collecting water from distant areas, domestic violence over the amount of water nerveless, and fights over scarce water supply.[82] A study in India, for case, found that women felt intense fear of sexual violence when accessing water and sanitation services. [83] A like study in Uganda likewise establish that women reported to feel a danger for their security whilst journeying to toilets particularly at night.[84]

Climate change [edit]

Climate change poses increased risk to WASH systems, detail in Sub-Saharan Africa where access to safely managed bones sanitation is low.[85] In Sub-Saharan Africa poorly managed WASH systems and widespread informal settlements with express access to water and sanitation infrastructure are specially vulnerable to climate extremes such every bit flooding.[86] [87] Changes in the frequency and intensity of climate extremes could compound current challenges equally water availability becomes uncertain, and wellness risks increase due to contaminated water sources.[88]

Climate alter proposes many difficulties and challenges for Wash initiatives around the earth. Particularly, climate change can cause in a subtract of water availability, an increase of water necessity, damage to WASH facilities, increased water contamination from pollutants, etc.[89]

Global goals, planning and monitoring [edit]

Sustainable Evolution Goal Number half dozen [edit]

Since 1990, the Joint Monitoring Plan (JMP) for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene by WHO and UNICEF has regularly produced estimates of global Launder progress.[seven] [66] The JMP was responsible for monitoring the Un'southward Millennium Development Goal (MDG) Target 7.C, which aimed to "halve, past 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safety drinking water and basic sanitation".[xc] This has been replaced past the 2030 Sustainable Evolution Goals (SDG), where Goal half dozen aims to "ensure availability and sustainable direction of h2o and sanitation for all".[ii]

The JMP is responsible for tracking progress toward those SDG 6 Targets focused on improving the standard of WASH services, including Target 6.1 which is: "by 2030, reach universal and equitable access to prophylactic and affordable drinking water for all"; and Target 6.ii which is: "by 2030, reach access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all, and end open defecation, paying special attending to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations".[91] In addition, the JMP collaborates with other organizations and agencies responsible for monitoring other Wash-related SDGs, including SDG Target 1.4 on improving access to basic services, SDG Target 3.nine on reducing deaths and illnesses from unsafe water, and SDG Target 4.a on building and upgrading adequate Launder services in schools.[91]

To plant a reference betoken from which progress toward achieving the SDGs could be monitored, the JMP produced "Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2022 Update and SDG Baselines".[seven] According to this written report, 844 million people still lacked even a basic drinking water service in 2017.[seven] : 3 Of those, 159 million people worldwide drink water directly from surface water sources, such as lakes and streams.[7] : 3

In addition, the JMP written report found that, globally, iv.5 billion people do non have toilets at domicile that tin safely manage waste despite improvements in access to sanitation over the past decades.[vii] Approximately 600 million people share a toilet or latrine with other households and 892 million people practice open defecation.[7] Furthermore, just 1 in 4 people in low-income countries have handwashing facilities with soap and h2o at home; just xiv% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa take handwashing facilities.[7] Worldwide, at least 500 million women and girls lack adequate, safety, and private facilities for managing menstrual hygiene.[92]

-

Distributing jerrycans to assistance people store clean drinking water in the Philippines

-

Women line up at a diameter hole to fill their containers with water (Labuje IDP military camp, Kitgum, Kitgum Commune, Northern Region of Uganda)

Planning approaches [edit]

National Wash plans and monitoring [edit]

United nations-Water carries out the "Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS)" initiative. This piece of work examines the "extent to which countries develop and implement national policies and plans for WASH, conduct regular monitoring, regulate and take corrective action equally needed, and coordinate these parallel processes with sufficient fiscal resources and support from strong national institutions."[93] In 2022 it was found that many countries' WASH plans are not supported past the necessary financial and human resource. This hinders their implementation and intended outcomes for Wash service delivery.[93]

Integrated water resource direction (IWRM) [edit]

In 1992, the United Nations proposed Integrated water resources management (IWRM) as a solution to Launder challenges and policy failures.[94] An integrated approach to water management aims to minimize challenges associated with h2o-borne affliction, water justice, poor compliance with prophylactic hygiene behaviors, and sustainability by involving stakeholders at every level of management and consumption. This approach also recognizes the political, economic, and social influence of Wash as well equally the need to coordinate water and sanitation management.[95] [96] Critics of current implementation of IWRM argue information technology has been externally imposed on developing countries and tin can be culturally inappropriate to the needs of private communities. Instead, a hybrid approach that includes greater community-level direction and flexibility but with the same goals every bit IWRM has been suggested.[94]

History [edit]

The history of water supply and sanitation is the topic of a separate article.

Abbreviation [edit]

The abridgement Wash was used from the year 1988 onwards equally an acronym for the "Water and Sanitation for Health" Projection of the United States Agency for International Development.[97] At that time, the alphabetic character "H" stood for "health", not "hygiene". Similarly, in Republic of zambia the term WASHE was used in a report in 1987 and stood for "H2o Sanitation Health Teaching".[98] An even older USAID "Wash project report" dates back to as early on as 1981.[99]

From about 2001 onwards, international organizations agile in the area of water supply and sanitation advancement, such every bit the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council and the International H2o and Sanitation Centre (IRC) in holland began to use "Wash" as an umbrella term for h2o, sanitation and hygiene.[100] "Launder" has since so been broadly adopted every bit a handy acronym for water, sanitation and hygiene in the international development context.[101] The term "WatSan" was also used for a while, especially in the emergency response sector such equally with IFRC and UNHCR,[102] only has not proven as popular as Launder.

Focus areas and trends [edit]

The United Nation'southward International Year of Sanitation in 2008 helped to increment attention for funding of sanitation in WASH programs of many donors. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has increased their funding for sanitation projects since 2009, with a strong focus on reuse of excreta.[103]

Social club and civilization [edit]

Awards [edit]

Several prizes are awarded for individuals or organizations working on Wash, notably:

- The Stockholm Water Prize since 1991, with a broad-ranging view of water-related activities, along with the Stockholm Inferior Water Prize and the Stockholm Manufacture Water Award.

- The University of Oklahoma International H2o Prize since 2009, for WASH activities in developing countries.

- The Sarphati Sanitation Awards since 2013, for sanitation entrepreneurship.

United nations organs [edit]

- UNICEF - UNICEF's declared strategy is "to reach universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all".[104] UNICEF includes Wash initiatives in their piece of work with schools in over xxx countries.[105]

- UN-H2o

Awareness raising [edit]

Sensation raising for the importance of WASH is regularly carried out past diverse organizations through their publications and activities on certain special days of the year (United Nations international observance days), namely: Globe Water Solar day for water (22 March), World Toilet Day for sanitation (nineteen Nov) and Global Handwashing Day for hygiene (fifteen October).

See also [edit]

- Child mortality

- History of water supply and sanitation

- Homo right to water and sanitation

- Mass deworming

- H2o problems in developing countries

International networks and partnerships

- Global Water Security & Sanitation Partnership

- Sanitation and Hygiene Fund (formerly the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Quango)

- Sanitation and Water for All

- Sustainable Sanitation Brotherhood

References [edit]

- ^ "Mortality rate attributable to unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)". Our World in Information . Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Goal six .:. Sustainable Development Noesis Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org . Retrieved 2017-eleven-17 .

- ^ Kooy, M. and Harris, D. (2012) Briefing paper: Political economy analysis for water, sanitation and hygiene (Wash) service commitment. Overseas Development Institute

- ^ a b c "Water, Sanitation & Hygiene: Strategy Overview". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation . Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Cardinal facts from JMP 2022 report". World Health Organisation. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved 2017-11-17 .

- ^ "WHO | Lack of sanitation for 2.4 billion people is undermining health improvements". world wide web.who.int. Archived from the original on July ii, 2015. Retrieved 2017-11-17 .

- ^ a b c d e f k h i WHO, UNICEF (2017). Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene : 2022 update and SDG baselines. Geneva. ISBN978-9241512893. OCLC 1010983346.

- ^ a b "Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: Introduction". UNICEF. UNICEF. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Guidelines on sanitation and health. Geneva: World Wellness Organization. 2018. ISBN9789241514705. OCLC 1104819635.

- ^ Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J (2002). "Estimating the burden of affliction from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level" (PDF). Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (5): 537–42. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110537. PMC1240845. PMID 12003760.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Call to action on sanitation" (PDF). United nations . Retrieved 15 Baronial 2014.

- ^ Spears, Dean; Ghosh, Arabinda; Cumming, Oliver (2013). "Open up Defecation and Babyhood Stunting in Republic of india: An Ecological Analysis of New Data from 112 Districts". PLOS ONE. eight (nine): e73784. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873784S. doi:ten.1371/journal.pone.0073784. PMC3774764. PMID 24066070.

- ^ a b c Johnston, R., Prüss-Ustün, A., Wolf, J. (2019). Safer Water, Improve Health. Globe Health System (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland, ISBN 978-92-iv-151689-1

- ^ Gleick, P. (2002) Muddied Water: Estimated Deaths from Water-Related Diseases 2000–2020, Pacific Constitute for Studies in Development, Surround, and Security

- ^ WHO (2014) Soil-transmitted helminth infections, Fact sheet Northward°366

- ^ a b c d east f g h i "Diarrhoeal disease Factsheet". Earth Health Organization. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Abdelmalak B, Doyle J, eds. (2013). Anesthesia for otolaryngologic surgery. Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–287. ISBN978-1-107-01867-9.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with inability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-iv. PMC4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex activity specific all-crusade and cause-specific bloodshed for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Illness Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b "Global Diarrhea Burden". CDC. 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on vii July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ Walker, CL; Rudan, I; Liu, Fifty; Nair, H; Theodoratou, Due east; Bhutta, ZA; O'Brien, KL; Campbell, H; Black, RE (20 Apr 2013). "Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea". Lancet. 381 (9875): 1405–16. doi:ten.1016/S0140-6736(xiii)60222-6. PMC7159282. PMID 23582727.

- ^ "WHO | Diarrhoeal illness". Who.int. Retrieved 2014-03-10 .

- ^ Spears, Dean; Ghosh, Arabinda; Cumming, Oliver (2013-09-16). "Open Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India: An Ecological Analysis of New Data from 112 Districts". PLOS ONE. eight (nine): e73784. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873784S. doi:x.1371/journal.pone.0073784. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC3774764. PMID 24066070.

- ^ Mara, Duncan (2017). "The elimination of open defecation and its adverse health furnishings: a moral imperative for governments and development professionals". Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Evolution. seven (1): 1–12. doi:10.2166/washdev.2017.027. ISSN 2043-9083.

- ^ a b Wolf, Jennyfer; Prüss-Ustün, Annette; Cumming, Oliver; Bartram, Jamie; Bonjour, Sophie; Cairncross, Sandy; Clasen, Thomas; Colford, John Thou.; Curtis, Valerie; De France, Jennifer; Fewtrell, Lorna; Freeman, Matthew C.; Gordon, Bruce; Hunter, Paul R.; Jeandron, Aurelie; Johnston, Richard B.; Mäusezahl, Daniel; Mathers, Colin; Neira, Maria; Higgins, Julian P.T. (August 2014). "Systematic review: Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and centre-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression" (PDF). Tropical Medicine & International Health. 19 (8): 928–42. doi:10.1111/tmi.12331. PMID 24811732. S2CID 22903164.

- ^ "Diarrhoeal affliction Fact sheet". World Health System. two May 2017. Retrieved 29 Oct 2020.

- ^ JMP (2008) World Health Organization and UNICEF. Progress on Drinking H2o and Sanitation: Special Focus on Sanitation., ISBN 978 92 806 4313 eight

- ^ a b Prüss-Üstün, A., Bos, R., Gore, F., Bartram, J. (2008). Safer water, amend health – Costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Wellness Arrangement (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland

- ^ a b Johnston, East. Anna; Teague, Hashemite kingdom of jordan; Graham, Jay P (2015). "Challenges and opportunities associated with neglected tropical disease and water, sanitation and hygiene intersectoral integration programs". BMC Public Health. xv: 547. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1838-7. PMC4464235. PMID 26062691.

- ^ Freeman, Matthew C.; Ogden, Stephanie; Jacobson, Julie; Abbott, Daniel; Addiss, David K.; Amnie, Asrat G.; Beckwith, Colin; Cairncross, Sandy; Callejas, Rafael; Colford, Jack M.; Emerson, Paul M. (2013-09-26). Liang, Vocal (ed.). "Integration of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene for the Prevention and Command of Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Rationale for Inter-Sectoral Collaboration". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (9): e2439. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002439. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC3784463. PMID 24086781.

- ^ "WHO strengthens focus on h2o, sanitation and hygiene to accelerate emptying of neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organisation (WHO). 27 August 2015. Archived from the original on Baronial 31, 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ Earth Health System (WHO) (2015): H2o Sanitation and Hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on Neglected Tropical Diseases. A global strategy 2022 - 2020. Geneva, Switzerland, p. 26.

- ^ World Health Organization (WHO) (2012). Accelerating work to overcome the global touch on of Neglected Tropical Diseases. A raodmap for implementation. Geneva, Switzerland.

- ^ "Poster on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) for accelerating and sustaining progress on NTDs" (PDF). World Wellness Organisation (WHO). 27 August 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Cairncross, S; Hunt, C; Boisson, Southward; Bostoen, 1000; Curtis, Five; Fung, I. C; Schmidt, W. P (2010). "Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39: i193–205. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq035. PMC2845874. PMID 20348121.

- ^ a b Waddington, Hugh; Snilstveit, Birte; White, Howard; Fewtrell, Lorna (2012). "Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions to combat childhood diarrhoea in developing countries". Journal of Evolution Effectiveness. doi:10.23846/sr0017.

- ^ a b c Fewtrell, Lorna; Kaufmann, Rachel B; Kay, David; Enanoria, Wayne; Haller, Laurence; Colford, John M (2005). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 42–52. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. PMID 15620560.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Dawn L; Kahawita, Tanya M; Cairncross, Sandy; Ensink, Jeroen H. J (2015). "The Impact of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Interventions to Control Cholera: A Systematic Review". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135676. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035676T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135676. PMC4540465. PMID 26284367.

- ^ Cutler, David M; Miller, Grant (2005). "The Role of Public Health Improvements in Wellness Advances: The Twentieth-Century U.s.a.". Demography. 42 (1): i–22. doi:x.1353/dem.2005.0002. PMID 15782893. S2CID 35536095.

- ^ Clasen, Thomas F.; Alexander, Kelly T.; Sinclair, David; Boisson, Sophie; Peletz, Rachel; Chang, Howard H.; Majorin, Fiona; Cairncross, Sandy (2015-ten-20), "Interventions to improve water quality for preventing diarrhoea", The Cochrane Library, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, no. 10, pp. CD004794, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004794.pub3, PMC4625648, PMID 26488938

- ^ Tsesmelis, D.E., Skondras, N.A., Khan, South.Y.A. et al. H2o, Sanitation and Hygiene (Launder) Index: Evolution and Application to Measure Launder Service Levels in European Humanitarian Camps. Water Resour Manage 34, 2449–2470 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-020-02562-z

- ^ Toonen J, Akwataghibe N, Wolmarans Fifty, Wegelin G. Evaluation of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) within the UNICEF Country Programme of Cooperation Final Written report [Cyberspace]. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct three]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Nigeria_Impact_Evaluation_of_WASH_within_the_UNICEF_Country_Programme_of_Cooperation_Report.pdf

- ^ a b United Nations Children's Fund, Raising Even More Clean Easily: Advancing Learning, Wellness and Participation through WASH in Schools, New York: UNICEF, 2012

- ^ a b Agol, Dorice; Harvey, Peter; Maíllo, Javier (2018-03-01). "Sanitation and water supply in schools and girls' educational progression in Zambia". Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Evolution. 8 (i): 53–61. doi:10.2166/washdev.2017.032. ISSN 2043-9083.

- ^ a b c Koolwal, Gayatri; Van de Walle, Dominique (May 2010). Access to Water, Women's Work and Child Outcomes (PDF). The World Bank.

- ^ a b c Dauenhauer, Thousand., Schlenk, J., Langkau, T. (2016). Managing WASH in Schools: Is the Pedagogy Sector Ready? - A Thematic Discussion Series hosted by GIZ and SuSanA. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance, Frg

- ^ UNESCO (2014). "Puberty Education and Menstrual Hygiene Management" (PDF). UNESCO.

- ^ Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: India country report. WaterAid. [ page needed ]

- ^ Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH research: Pakistan country written report. WaterAid. [ page needed ]

- ^ Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). Schoolhouse Wash research: Nepal country report. WaterAid. [ page needed ]

- ^ Tiberghien, Jacques-Edouard (2016). School WASH inquiry: Bangladesh state report. WaterAid. [ page needed ]

- ^ UNICEF, GIZ (2016). Scaling up group handwashing in schools - Compendium of group washing facilities across the globe. New York, United states of america; Eschborn, Frg

- ^ UNICEF (2012) Raising Even More than Make clean Hands: Advancing Wellness, Learning and Equity through Wash in Schools, Joint Phone call to Activity

- ^ School Community Manual - Indonesia (formerly Manual for teachers), Fit for Schoolhouse. GIZ Fit for Schoolhouse, Philippines. 2014. ISBN978-iii-95645-250-5.

- ^ GIZ Fit for School. Field Guide: Hardware for Grouping Handwashing in Schools. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Philippines. ISBN978-3-95645-057-0. [ folio needed ]

- ^ United nations-Water. "Handwashing/Hand hygiene". UN-Water . Retrieved 2021-05-13 .

- ^ Un-Water. "Handwashing/Mitt hygiene". United nations-Water . Retrieved 2021-05-thirteen .

- ^ a b c Water, sanitation and hygiene in health intendance facilities Earth Health Organization (2015) [1] Retrieved 3 Oct 2017.

- ^ a b WHO (2019) Water, sanitation and hygiene in wellness intendance facilities: practical steps to achieve universal admission. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC Past-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- ^ a b c d Monitoring WASH in Wellness Care Facilities. World Health Organization (2016). http://world wide web.who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/coverage/wash-in-hcf-core-questions.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities in Asia and the Pacific. WaterAid (2015).http://www.wateraidamerica.org/publications/water-sanitation-and-hygiene-in-health-care-facilities-in-asia-pacific Retrieved three October 2017.

- ^ The claiming of slums: global report on man settlements 2003 (PDF). London: United Nations Global Settlements Plan. 2003. p. xxvi. ISBN978-1-84407-037-4 . Retrieved 27 Feb 2020.

- ^ Duflo, Esther; Galiani, Sebastian; Mobarak, Mushfiq (October 2012). Improving Access to Urban Services for the Poor: Open up Issues and a Framework for a Future Research Agenda (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Activity Lab. p. 5. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ a b Moe, Christine L.; Rheingans, Richard D. (July 2006). "Global challenges in water, sanitation and wellness" (PDF). Journal of Water and Wellness. 4 (S1): 41–57. doi:10.2166/wh.2006.0043. ISSN 1477-8920. PMID 16493899.

- ^ Carter, R. C.; Tyrrel, S. F.; Howsam, P. (Baronial 1999). "The Bear upon and Sustainability of Community Water Supply and Sanitation Programmes in Developing Countries". Water and Environment Journal. 13 (4): 292–296. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.1999.tb01050.x. ISSN 1747-6585.

- ^ a b c d east UNICEF and WHO (2019). Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2017. Special focus on inequalities. New York: United Nations Children'southward Fund (UNICEF) and Globe Wellness Organization

- ^ "Women 2000 and beyond Women and Water" (2005) UNITED NATIONS, Division for the Advancement of Women, Section of Economic and Social Diplomacy

- ^ "The Dublin statement". world wide web.wmo.int . Retrieved 2020-02-21 .

- ^ Un-H2o (2006) Gender, Water and Sanitation: A Policy Cursory

- ^ WaterAid Canada (2019). Water, sanitation and hygiene - A Pathway to Realizing Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls. WaterAid Canada

- ^ a b Sidhu, K., Grossman, A., Johnson, Northward. (2003) "Diverting the Catamenia: A Resource Guide to Gender, Rights and Water Privatization", Women's Environs and Development Organization.

- ^ Crow, Ben; Odaba, Edmond (November 2010). "Access to Water in a Nairobi Slum: Women'south Work and Institutional Learning" (PDF). Water International. 35 (6): 733–747. doi:10.1080/02508060.2010.533344. S2CID 153289383.

- ^ a b Keefer, Natalie; Bousalis, Rina (Jan 2015). "How Practise You Become Your Water? Structural Violence Pedagogy and Women'southward Access to Water". Social Studies. 106 (6): 256–263. doi:10.1080/00377996.2015.1072793. S2CID 143162763.

- ^ a b CAP-NET, GWA (2006). Why gender matters - A tutorial for water managers. Multimedia CD and booklet. CAP-NET International network for Chapters Building in Integrated Water Resources Management, Delft.

- ^ a b Globe Bank (2019). Women in H2o Utilities - Breaking Barriers. World Bank, Washington, DC

- ^ United nations Water (2005) "A Gender Perspective on H2o Resources and Sanitation", Interagency Task Force on Gender and Water, United nations Section of Economical and Social Affairs

- ^ Worldbank (1996) Toolkit on Gender in Water and Sanitation. Gender Toolkit Series Number 2

- ^ UN Water Activities

- ^ a b Chancellor F., Hussein Thousand., Lidonde R. A, Mustafa D. and Van Wijk C. Editors: Appleton B. and Smout I. (2003) The Gender and H2o Development Report 2003: Gender Perspectives on Policies in the H2o Sector, Gender and Water Alliance, ISBN Paperback 1 84380 021 7

- ^ "Gender". UN-Water . Retrieved 21 Feb 2020.

- ^ Business firm, S., Ferron, Southward., Sommer, Yard., Cavill, South. (2014). Violence, Gender and WASH: A Practitioner's Toolkit - Making h2o, sanitation and hygiene safer through improved programming and services. London, Uk: WaterAid/SHARE

- ^ Sommer, Marni; Ferron, Suzanne; Cavill, Sue; Business firm, Sarah (2015). "Violence, gender and Launder: spurring action on a complex, nether-documented and sensitive topic". Environs and Urbanization. 27 (1): 105–116. doi:ten.1177/0956247814564528. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 70398487.

- ^ "Improving Wash, Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence". WASHfunders . Retrieved 2021-05-13 .

- ^ "Improving Launder, Reducing Vulnerabilities to Violence". WASHfunders . Retrieved 2021-05-13 .

- ^ "JMP". washdata.org . Retrieved 2020-11-25 .

- ^ Joubert, Leonie. "URBAN FLOOD STORIES PAINT FULLER Moving picture OF CLIMATE RISK IN East AFRICAN CITIES".

- ^ "Africa Water Week 2018: Inclusive urban WASH services under climate change". Future Climate For Africa . Retrieved 2020-11-25 .

- ^ "Climate modify | Wash Matters". washmatters.wateraid.org . Retrieved 2020-xi-25 .

- ^ "Climate Modify Response for Inclusive WASH: A guidance note for Plan International Republic of indonesia, Guidance Note - December 2022 - Indonesia". ReliefWeb . Retrieved 2021-05-xiii .

- ^ "Goal seven: Ensure Ecology Sustainability". United Nations Millennium Development Goals website . Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b United Nations (2015). Transforming our earth the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development : A/RES/70/one. Un, Division for Sustainable Development. OCLC 973387855.

- ^ "Menstrual Hygiene Direction Enables Women and Girls to Reach Their Full Potential". World Banking company . Retrieved 2018-12-01 .

- ^ a b WHO, UN-H2o (2019). UN-H2o Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS) 2022 Study - National systems to support drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene - Global status report 2019. Globe Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland

- ^ a b Butterworth, John (2010). "Finding applied approaches to integrated water resource management". Water Alternatives. 3 (ane): 68–81.

- ^ Tilley, Elizabeth; Strande, Linda; Lüthi, Christoph; Mosler, Hans-Joachim; Udert, Kai One thousand.; Gebauer, Heiko; Hering, Janet G. (2014-09-02). "Looking beyond Technology: An Integrated Approach to H2o, Sanitation and Hygiene in Low Income Countries". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (17): 9965–9970. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.9965T. doi:x.1021/es501645d. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 25025776.

- ^ Dreibelbis, Robert; Winch, Peter J; Leontsini, Elli; Hulland, Kristyna RS; Ram, Pavani G; Unicomb, Leanne; Luby, Stephen P (Dec 2013). "The Integrated Behavioural Model for H2o, Sanitation, and Hygiene: a systematic review of behavioural models and a framework for designing and evaluating behaviour modify interventions in infrastructure-restricted settings". BMC Public Wellness. 13 (1): 1015. doi:ten.1186/1471-2458-thirteen-1015. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC4231350. PMID 24160869.

- ^ "Launder Technical Report No 37" (PDF). USAID. 1988. Retrieved 2015-12-30 .

- ^ WASHE (Water Sanitation Health Education) in Republic of zambia (1987). Participatory health didactics: ready for utilize materials: design and production WASHE programme. WASHE Western Province, Zambia. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ WASH Technical Report No 7 (1981). Facilitation of community organization: an approach to water and sanitation programs in developing countries (WASH Chore No 94): prepared for USAID. USAID/Launder Washington DC, USA. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Jong, D. de (2003) Advancement for water, environmental sanitation and hygiene - Thematic overview newspaper, IRC, Holland

- ^ "Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion" (PDF). WHO.int. 2005. Retrieved 2015-12-17 .

- ^ UNHCR Division of Operational Services (2008). A Guidance for UNHCR Field Operations on H2o and Sanitation Services. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved xi March 2016.

- ^ Elisabeth von Muench, Dorothee Spuhler, Trevor Surridge, Nelson Ekane, Kim Andersson, Emine Goekce Fidan, Arno Rosemarin (2013) Sustainable Sanitation Alliance members have a closer look at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's sanitation grants, Sustainable Sanitation Practice Journal, Issue 17, p. 4-10

- ^ UNICEF Strategy for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene 2016-2030, accessible online at https://world wide web.unicef.org/wash/files/UNICEF_Strategy_for_WASH_2016-2030.pdf

- ^ "H2o, sanitation and education | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UNICEF".

External links [edit]

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) - UNHCR website

- Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Home - Healthy Water - Centres for Affliction Command and Prevention website

- Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WASH

0 Response to "What Is the Best Way to Wash a House"

Post a Comment